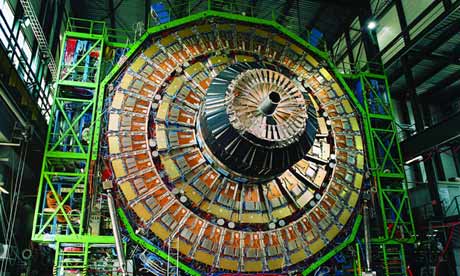

The Large Hadron Collider was built in the pursuit of pure science, but research into quantum mechanics might soon yield enormous benefits for computing. Photograph: Rex Features

Our imagination is stretched to the utmost," wrote Richard Feynman, the greatest physicist of his day, "not, as in fiction, to imagine things which are not really there, but just to comprehend those things that are there." Which is another way of saying that physics is weird. And particle physics– or quantum mechanics, to give it its posh title – is weird to the power of n, where n is a very large integer.

Consider some of the things that particle physicists believe. They accept without batting an eyelid, for example, that one particular subatomic particle, the neutrino, can pass right through the Earth without stopping. They believe that a subatomic particle can be in two different states at the same time. And that two particles can be "entangled" in such a way that they can co-ordinate their properties regardless of the distance in space and time that separates them (an idea that even Einstein found "spooky"). And that whenever we look at subatomic particles they are altered by the act of inspection so that, in a sense, we can never see them as they are.

For a long time, the world looked upon quantum physicists with a kind of bemused affection. Sure, they might be wacky, but boy, were they smart!And western governments stumped up large quantities of dosh to enable them to build the experimental kit they needed for their investigations. A huge underground doughnut was excavated in the suburbs of Geneva, for example, and filled with unconscionable amounts of heavy machinery in the hope that it would enable the quark-hunters to find the Higgs boson, or at any rate its shadowy tracks.

All of this was in furtherance of the purest of pure science – curiosity-driven research. The idea that this stuff might have any practical application seemed, well, preposterous to most of us. But here and there, there were people who thought otherwise (among them, as it happens, Richard Feynman). In particular, these visionaries wondered about the potential of harnessing the strange properties of subatomic particles for computational purposes. After all, if a particle can be in two different states at the same time (in contrast to a humdrum digital bit, which can only be a one or a zero), then maybe we could use that for speeded-up computing. And so on.

Thus was born the idea of the "quantum computer". At its heart is the idea of a quantum bit or qubit. The bits that conventional computers use are implemented by transistors that can either be on (1) or off (0). Qubits, in contrast, can be both on and off at the same time, which implies that they could be used to carry out two or more calculations simultaneously. In principle, therefore, quantum computers should run much faster than conventional, silicon-based ones, at least in calculations where parallel processing is helpful.

For as long as I have been paying attention to this stuff, the academic literature has been full of arguments about quantum computing. Some people thought that while it might be possible in theory, in practice it would prove impracticable. But while these disputes raged, a Canadian company called D-Wave – whose backers include Amazon boss Jeff Bezos and the "investment arm" of the CIA (I am not making this up) – was quietly getting on with building and marketing a quantum computer. In 2011, D-Wave sold its first machine – a 128-qubit computer – to military contractor Lockheed Martin. And last week it was announced that D-Wave had sold a more powerful machine to a consortium led by Google and Nasa and a number of leading US universities.

What's interesting about this is not so much its confirmation that the technology may indeed be a practical proposition, though that's significant in itself. More important is that it signals the possibility that we might be heading for a major step change in processing power. In one experiment, for example, it was found that the D-Wave machine was 3,600 times faster than a conventional computer in certain kinds of applications. Given that the increases in processing power enabled by Moore's law (which applies only to silicon and says that computing power doubles roughly every two years) are already causing us to revise our assumptions about what computers can and cannot do, we may have some more revisions to do. All of which goes to prove the truth of the adage: pure research is just research that hasn't yet been applied.

0 comentários:

Postar um comentário